The great e-cigarette war

E-cigarettes are far less harmful than tobacco and could be prescribed to help smokers quit, a report in England found. But the Welsh government wants to ban their use in public places. Why are approaches in the neighbouring countries so different?

Some look like traditional cigarettes, with a light to mimic the glow of burning ash. Others are more ornate – long metallic devices that more closely resemble pipes or even torches.

These days you don’t have to go very far to spot one.

Around 2.6 million adults in Britain have used e-cigarettes in the decade or so that they have been on the market. And there’s wide disagreement about the extent to which this is a good or a bad thing.

No-one is advising non-smokers to take them up, but a recent report by Public Health England and found they were 95% less harmful than tobacco and could be a “game changer” when it came to persuading people to quit cigarettes.

And yet while the report heralded the possibility of prescribing e-cigarettes to English smokers who want to stop, neighbouring Wales is taking quite a different approach.

The devolved government there is looking to ban them in enclosed public places – in common with 40 other countries that have already imposed similar restrictions. The World Health Organization also supports regulating them more stringently. Scotland has not gone as far as Wales, but e-cigarettes are currently forbidden in almost all Scottish hospital grounds, which the Holyrood government plans to put on a statutory footing.

E-cigarettes are not covered by the UK’s anti-smoking laws, and they are permitted in some pubs. But many businesses and organisations have imposed their own restrictions.

All Bar One, Caffe Nero, KFC and Starbucks are among the food chains that have banned them on their premises. Manchester City, Manchester United and Chelsea forbid using them in their stadia although Burnley FC has a “vaping zone”.

Pub chains Mitchell’s and Butlers, JD Wetherspoon and Fuller’s have all banned e-cigarette use on the premises, citing the possibility of confusion for customers and staff. Stonegate Pub Company said they were not allowed in non-smoking areas because of their “remarkable likeness” to cigarettes. Enterprise Inns leaves the decision down to its tenants and has done a deal with one brand of e-cigarettes to sell them.

The devices are forbidden on National Express coaches as well as on CrossCountry Trains, Northern, Thameslink and Virgin as well as all Transport for London routes. Many train stations ban their use even on open platforms as they can “unsettle passengers” and leave them thinking actual smoking is allowed.

Most airlines and airports ban them although London Heathrow permits their use up to the flight gate and Ryanair sells its own “smokeless” cigarettes, which aren’t electronic and work like nicotine inhalers. This year the industry body Oil and Gas UK advised companies not to allow e-cigarettes to be used offshore following a health and safety report.

Opinion is divided among UK public health professionals. The anti-smoking charity Ash strongly backed the PHE report’s recommendations and the Royal College of Physicians believes they could lead to “significant falls” in smoking. But the British Medical Association (BMA) supports banning their use in enclosed public places.

There is some consensus, however. The weight of evidence suggests that e-cigarettes – which heat liquid nicotine to form a vapour – are much less harmful to chronic smokers than conventional tobacco smoke, which has far higher levels of carcinogens and toxicants.

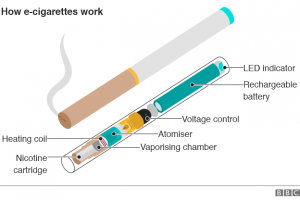

- On some e-cigarettes, inhalation activates the battery-powered atomiser. Other types are manually switched on

- A heating coil inside the atomiser heats liquid nicotine contained in a cartridge

- The mixture becomes vapour and is inhaled. Many e-cigarettes have an LED light as a cosmetic feature to simulate traditional cigarette glow.

Different brands of e-cigarettes contain different chemical concentrations.

But nor does anyone believe e-cigarettes are without risks. The PHE report acknowledges there are no studies on what harmful effects might result from long-term use. Official advice is to give up completely.

“No research has said these products are completely safe and efficient – the comparison is with the known risks of smoking,” says Ann McNeill, professor of tobacco addiction at Kings College London and one of the PHE report’s authors.

But it did find that e-cigarettes cause just a fraction of the harm done by tobacco cigarettes. Most of the chemicals which cause smoking-related diseases are not present in e-cigarettes and they contain only 1/50th of the formaldehyde of conventional cigarettes. They also release so little nicotine into ambient air that the risks to passers-by are marginal, the PHE team concluded.

The researchers also said e-cigarettes may be contributing to falling smoking rates, that there was no evidence so far they acted as a “gateway” to tobacco – and that half of people were unaware they they were less harmful than conventional smoking.

While it was not clear whether e-cigarettes were more or less effective than other stop-smoking medications, the fact the devices were more popular offered “an opportunity to expand the number of smokers stopping successfully”. PHE says they have helped 1.1 million people stop smoking.

But not everyone was convinced. The Welsh government issued a statement warning of the risk that e-cigarettes might nonetheless “normalise” smoking, “especially for a generation who have grown up in a largely smoke-free society”. Previously, in 2014, Dame Sally Davies, the chief Medial Officer for England, also warned they risked “normalising” the practice.

It’s not an argument that sways McNeill. “The best test of normalisation is what happens to smoking rates in the population,” she says.

“We commented in our report that since the introduction of e-cigarettes to the market the smoking prevalence has continued to decline.” Less than one in fiveEnglish adults was a smoker in 2013, down from 26% in 2003, a year before e-cigarettes entered the market.

The PHE report found that of the one in 20 adults in Great Britain who use e-cigarettes, about 60% are current tobacco smokers and the vast majority of the remainder are former smokers. Just 0.2% had never smoked.

There are other sources of scepticism. Some are concerned that the huge variety of the market means different e-cigarette brands deliver varying amounts of nicotine, toxins, and carcinogens. The BMA says there are “significant concerns from medical professionals around the inconsistent quality of e-cigarettes”.

In 2016, the EU’s Tobacco Products Directive will come into effect, however, which will tighten regulation on e-cigarettes and cap nicotine levels.

At present there are no e-cigarettes licensed through the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, so they cannot be prescribed by the NHS. If this were to change, says Rosanna O’Connor, director of alcohol, drugs and tobacco at PHE, medical regulation would result in e-cigarettes being made available alongside nicotine patches and gum and “provide reassurance of their quality and effectiveness”.

England’s policies towards e-cigarettes, which already are among the most liberal in the world, have much to do with a decision by the government’s Behavioural Insight Team – nicknamed the “nudge unit” – not to “regulate these out of existence” on the basis that they had the potential to reduce harm.

By contrast, Welsh policy was underpinned by a different set of assumptions. Julie Bishop, of Public Health Wales, has argued that, while there may be no conclusive evidence that children were taking up vaping in large numbers, the “precautionary principle” required “not waiting for conclusive evidence of harm” before taking action to protect young people.

Public health officials in England do not share this concern. “The evidence tells us that while there is some experimentation among young people, there is almost no regular use among young people or adults who have never smoked before,” says O’Connor.

The PHE report found around 13% of young people have tried them, but only 5% use them at least monthly and 0.5% weekly. Only 0.3% of young people who had never smoked before were regular e-cigarette users.

Bans on the sale of electronic cigarettes to under-18s are due to be introduced by authorities in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. But the different regimes appear to all have different philosophies when it comes to judging whether harm reduction should be a priority over minimising the risk of the devices.

Some objections are more visceral, based on the health professionals’ experience of the tobacco industry.

“My understanding of basic economic theory is that if it was bad for the big tobacco companies, they wouldn’t be doing it,” says David Bailey of the BMA’s Welsh GPs committee. “If these things are intended as a way to give up, why are they being marketed in 20 fruity flavours?”

Also, he asks whether it’s appropriate that taxpayers “should be funding someone’s lifelong addiction”.

The idea of “evidence-based policy” is a fashionable one. But while the evidence surrounding e-cigarettes is broadly accepted, there’s still much debate among decision-makers on what sort of policy should result from it.

Source : BBC